Ugly but Priceless: From Labubu to Crocs — 6 Weird Products That Turned Into Gold

How “Ugly” Sometimes Sells for Millions

In the world of trends, there’s a curious paradox: what looks “ugly” often becomes a must-have. Psychologists call this the uniqueness effect: if something is strange enough to stand out, and influencers pick it up, it’s destined for success. It’s because “I want it too” works stronger than “it looks nice.”

As psychotherapist Jordan Conrad explains:

“There is nothing in particular about Labubu dolls that makes them desirable, or justifies their appeal. In fact, they actively show off how useless and ugly they are — and that is what makes them so coveted.”

Economists add two important perspectives:

- David Lang calls Labubu a “cheap way to express status” in times of economic anxiety.

- Analysts at Owenomics describe it as a noisy analogue of speculative instruments, where artificial scarcity and hype push prices up — much like crypto or volatile funds.

After the announcement of mini-Labubu, Pop Mart’s stock jumped another 10–12%, hitting a record $40–41 per share. A single plush figure sold for more than $150,000 at auction.

And this isn’t the first time “ugly” has won. From Crocs to Beanie Babies, “ugly” has won before, and the latest proof of this trend is a figure named Labubu.

Labubu (Pop Mart)

Labubu is not just another blind-box figure — it’s the financial engine of Pop Mart. Its CEO, Wang Ning, said the company could surpass its annual revenue target of ¥20 billion ($2.78 bn) and even reach ¥30 billion ($4.18 bn) in 2025.

Such a growth came alongside aggressive international expansion: 571 offline stores and 2,600 “roboshops” across 18 countries have already been opened. Pop Mart’s stock soared by over 600% in a year; in 2025 alone, gains ranged from +257% to +600%.

As Ning told:

“We expect more restocking of existing series and launch of new editions to drive earnings expansion in the second half… For overseas markets we’re still very positive, and we believe there’s still broad space for growth.”

In other words, Labubu turned Pop Mart into Disney for Gen Z — from meme toy to global business, with ambitions stretching to animation, theme parks, and “mini-Labubu” phone charms as the next growth driver.

Still, financial charts don’t explain the core question — why are people willing to pay big money for something ‘ugly’?

To see the phenomenon through the eyes of consumers, the Gamblizard team conducted a survey of 1,000 respondents. We asked three key questions: who buys Labubu, how much they’re willing to spend on an ugly-cute toy, and what matters more — logic or emotion?

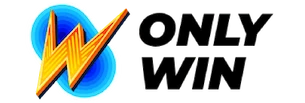

12% of Gen Z say Labubu is ugly, but still want to buy it

Subgroup sizes are not disclosed. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

The Labubu phenomenon isn’t about investment or logic. It’s about emotion, meme appeal, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) — forces that work just as well on those who call it ‘cute’ as on those who call it ‘weird.’

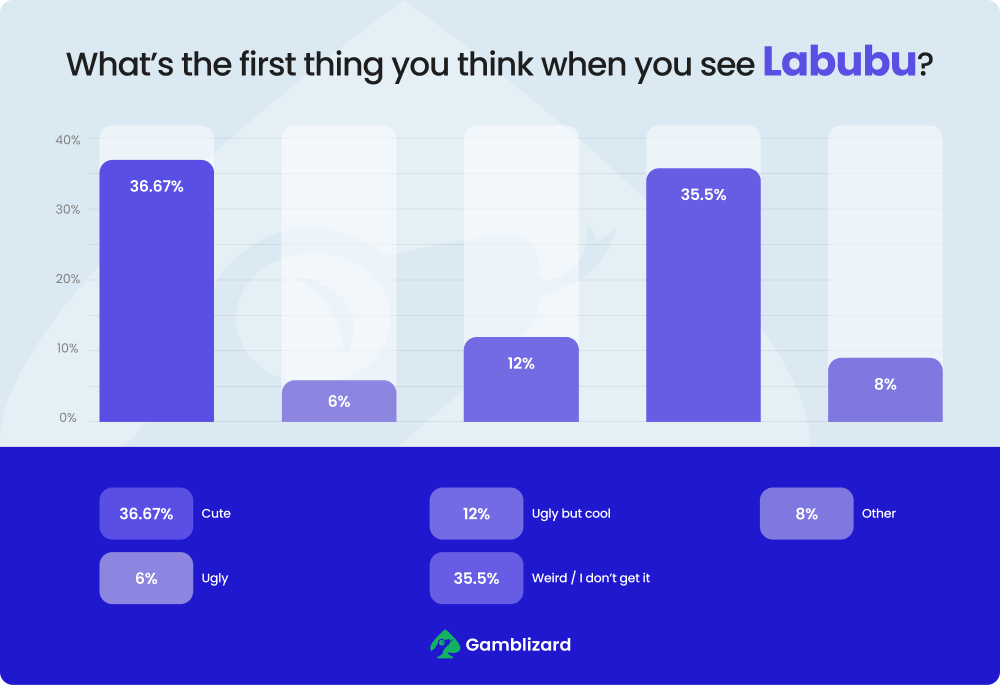

One-third (33%) say “emotion,” just 6% say “rational investment,” while 38% admit it’s both.

Some open-ended responses from the survey revealed the main purchase drivers:

- Nostalgia: ‘Reminds me of childhood toys’

- Identity signal: ‘Everyone has it’

- Dopamine hit: ‘Fun to unbox’

- Meme/irony: ‘So ugly it’s cute’

- Scarcity/FOMO: ‘Sold out fast’

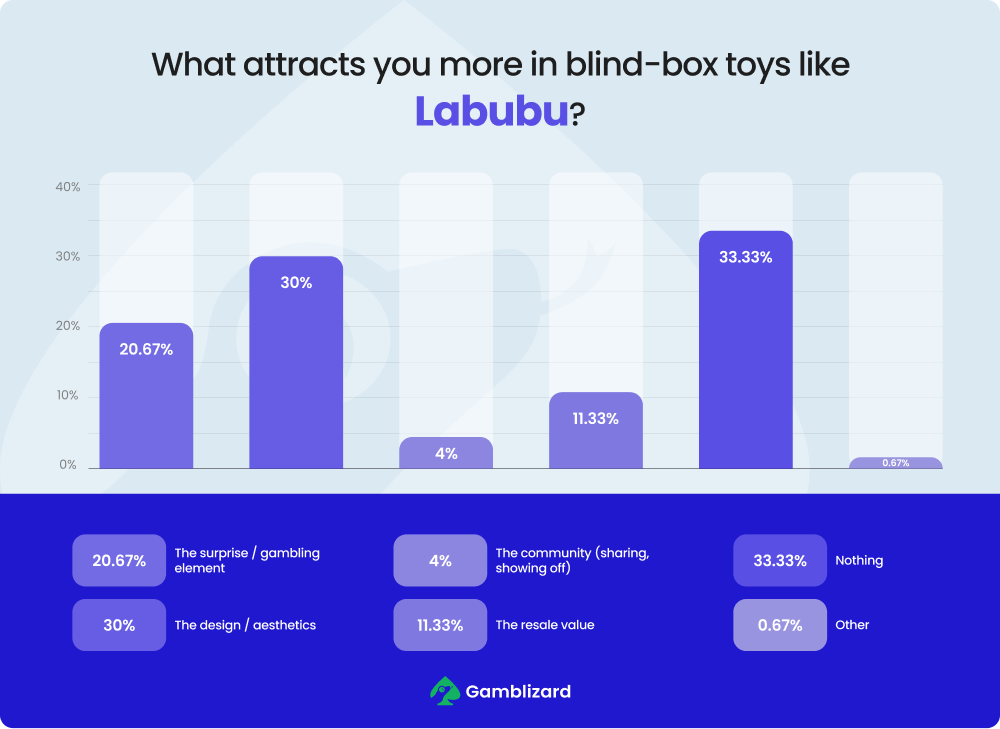

When asked what makes blind-box toys so attractive, 30% chose design/aesthetics and 21% the thrill of chance. Fewer pointed to community (4%) or resale value (11%).

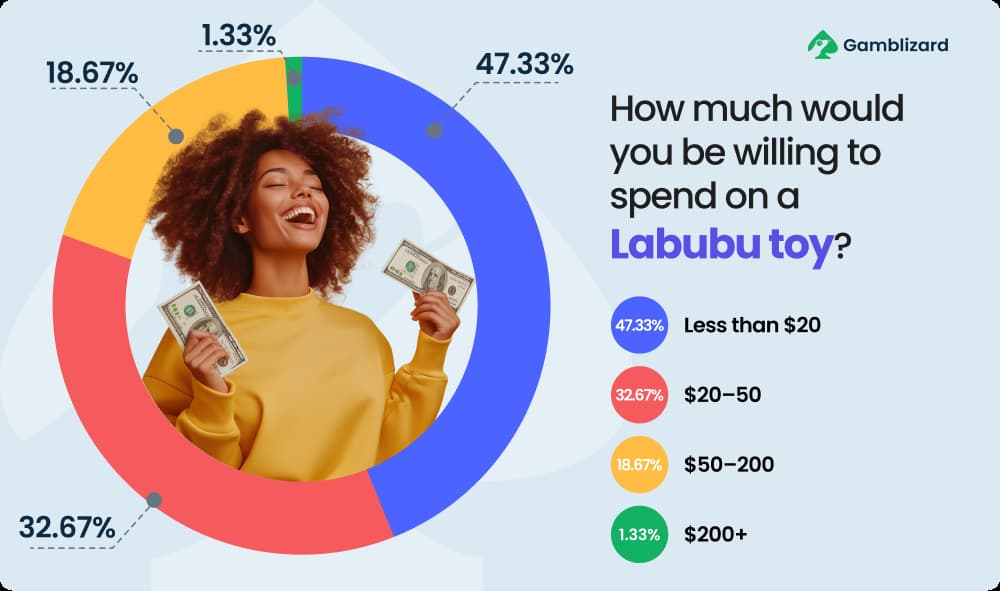

The spending sweet spot is clear: 47% would only pay up to $20, another 33% $20–50. Around 20% would go above $50, and fewer than 2% would spend over $200.

Such a statistics confirms what economists suggest: Labubu is a “cheap way to show status”, not luxury in the traditional sense. Or as one respondent put it: “So ugly it’s cute — and Instagram made me do it.”

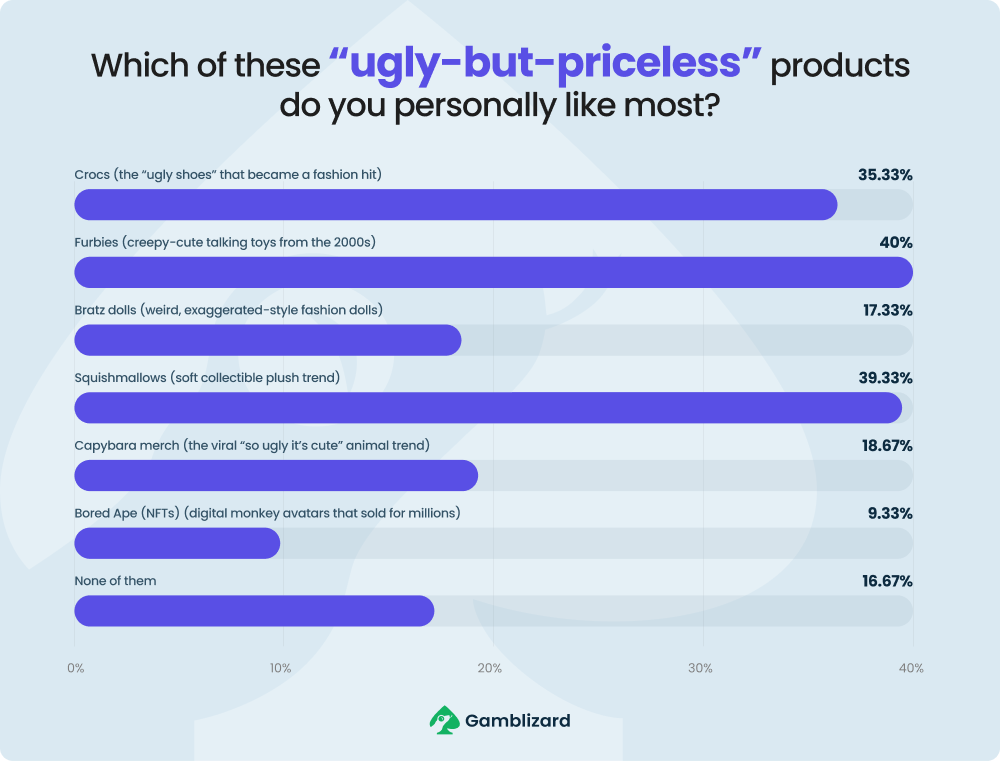

Labubu may be at its peak right now, but our survey showed the phenomenon is much broader. The respondents named other ugly-cute icons — from Furbies to Crocs. In other words, Labubu is just the latest chapter in a long-running story of products that look strange, even “wrong,” but become cult favorites over time. Here are some of the most striking examples.

Ugly works when it taps into childhood memories, provides comfort, or offers self-irony. That’s why Furbies and Crocs remain beloved, while NFT Bored Apes do not. At the same time, 16% of respondents said they don’t understand the ugly-cute trend at all — proof that it’s massive, but not universal.

Not Alone: 5 More Ugly-but-Priceless Hits

Labubu may be at its peak now, but it’s only the latest in a long tradition. Across decades, “weird” products have proven one thing: when logic says “no,” emotion and uniqueness can still turn into millions.

Crocs — Comfort Over Beauty

When Crocs debuted in 2002, they were ridiculed as “rubber monstrosities.” Yet by 2023, the company was earning more than $3 billion. Why? Because comfort and self-irony outweighed aesthetics. Ugly became a symbol of authenticity and prioritizing function over fashion.

Furbies — Creepy, But Alive

In the early 2000s, Furbies felt like horror-movie props, especially when they “talked” at night. However, that strangeness created a cult following: by 2000, more than 40 million units had been sold. Strong emotions — even discomfort — drive value.

Bratz Dolls — A Rebellion Against Barbie

With their exaggerated eyes and lips, Bratz were the polar opposite of Barbie. During the 2000s, over 2 billion dolls were sold, and the toy became a symbol of counterculture. They weren’t bought for perfect proportions, but for the chance to say: “I’m not like everyone else.”

Squishmallows — Comfort + Scarcity

Gen Z has built their own cult around squishy plush toys shaped like frogs, avocados, or vampire cats. In 2022, Squishmallows ranked among the top-10 best-selling toys worldwide, with sales topping $500 million. The formula here is simple: absurdly cute designs plus scarcity.

Capybara Merch — Memes as Marketing

TikTok videos of capybaras have racked up hundreds of millions of views, turning the animal into a symbol of calm. Hoodies, stickers, and plush toys featuring capybaras sell out fast as people buy into the global meme-club. Ugly-but-priceless now thrives on the power of memes: they don’t just sell, they create belonging and cultural context.

At the end of the day, this story isn’t about toys or shoes — it’s about us. People consistently choose emotion, laughter, nostalgia, and FOMO over beauty or rationality. That’s why the strange and the ugly keep turning into gold.